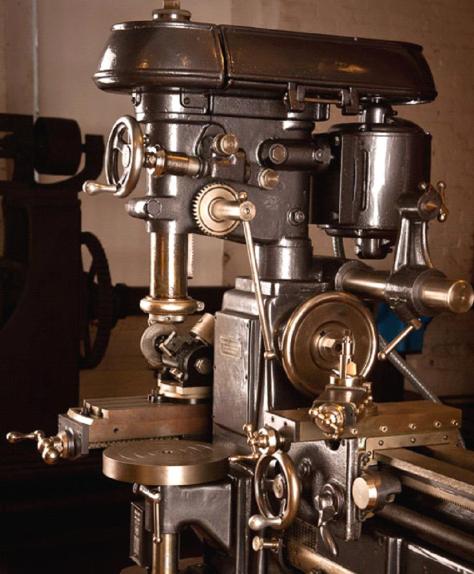

A Gilman Four-in-One milling machine from the collection at the amazing American Precision Museum in Windsor, VT. The only known surviving example (source here).

A Gilman Four-in-One milling machine from the collection at the amazing American Precision Museum in Windsor, VT. The only known surviving example (source here).

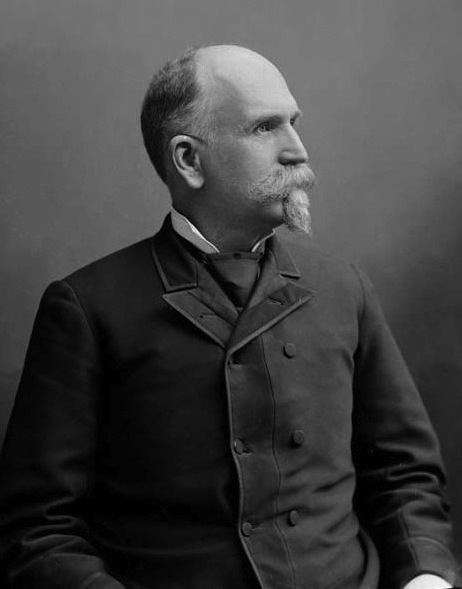

One hundred seventy three years ago on February 24, 1841, on a family farm in Westmoreland, New Hampshire, Levi Knight Fuller was born. A descendant of some of the earliest European settlers of New England, he landed squarely in the Victorian era, and personified the accomplishments of the Gilded Age in the United States. Fuller Steam Division is an historically grounded steampunk enterprise inspired by the life and times of this man, and is headquartered in his eventual hometown, Brattleboro, Vermont – on Fuller Drive, no less, on a remnant of his former estate.

Gov. Levi Knight Fuller 1841-1896 (bio on Wikipedia)

Gov. Levi Knight Fuller 1841-1896 (bio on Wikipedia)

Let’s take a quick look at this confluence of history and popular culture: what does the life of Levi K. Fuller, a once-prominent but now largely-forgotten Vermonter, have to do with the modern-day pop culture movement dubbed steampunk? Perhaps outlining the two will produce some correlations and comparisons. Steampunk is, after all, a multi-disciplinary genre which is drawn from historical antecedent and – right there – we are off to a good start! Steampunk has been defined in many ways, some more restrictive than others (which some might say flies in the face of its fantastic potential) but for simplicity let us refer to the most widely referenced statement on the subject, by the author G.D. Falksen.

A Victorian organ steampunked into a computer command center by the master Bruce Rosenbaum of ModVic in Sharon, MA. New England and Steampunk go together like pistons and connecting rods: see more of the regional oeuvre by Jake von Slatt, who took this photo.

A Victorian organ steampunked into a computer command center by the master Bruce Rosenbaum of ModVic in Sharon, MA. New England and Steampunk go together like pistons and connecting rods: see more of the regional oeuvre by Jake von Slatt, who took this photo.

Falksen’s “What Is Steampunk?” states summarily that Steampunk is Victorian science fiction (think of progenitors Jules Verne and H.G. Wells), but goes on to elaborate on what that might entail today. Basically, the idiom is grounded in the industrialized 19th century, extrapolated through modern eyes and experience to an imagination of what may have been, given that setting and mentality. An alternate or speculative history can be woven from the fabric of mechanical technology, social reconstruction, expanding scientific knowledge, and grand opportunity (albeit, not for all). With such a rich and diverse heritage of inspiration to draw from, a wide range of expression is enabled on many fronts: literature, fashion, applied technology, the fine arts, industrial design, the dramatic arts…

The Estey Organ Company complex: a National Register Historic Site on Birge St. in Brattleboro, VT Photo from FSD on Instagram

The Estey Organ Company complex: a National Register Historic Site on Birge St. in Brattleboro, VT Photo from FSD on Instagram

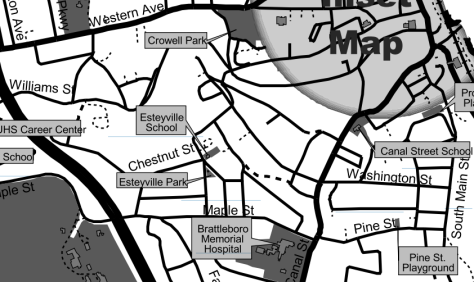

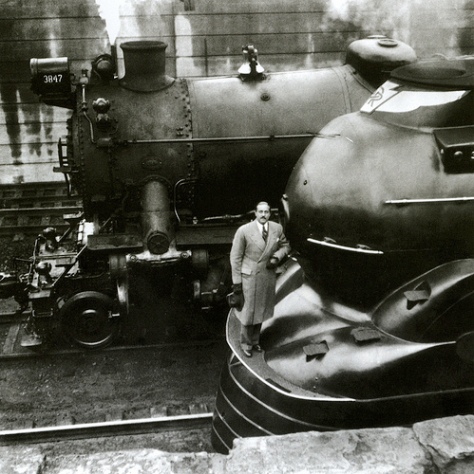

Levi Fuller was born into this time period and he epitomized many of its signature traits. A very brief enumeration: beginning a lifelong pursuit of knowledge at a very young age, he learned telegraphy and the printing trade at 13. With an early knack for science and engineering, he apprenticed with a firm in Boston at 16, returned to Brattleboro at 19 and found employment with Jacob Estey at his parlor organ manufactory. He proved his merit and rose quickly in the ranks, marrying his employer’s only daughter and becoming Vice-President of J. Estey and Co.; an indefatigable researcher, he had over 100 patents to his credit, and amassed a considerable fortune in the process. He founded and funded the Fuller Light Battery, a local militia unit; he collected what was considered the most complete technical and scientific library in the state of Vermont, alongside the finest equatorial telescope on the East coast, at his Pine Heights mansion on a hill above the town and near the organ factory. Philanthropist and benefactor, he championed and participated in several institutions of higher learning. He was elected handily to the office of Lieutenant Governor and then Governor of Vermont, and initiated many lasting and significant innovations on behalf of his beloved State. He is credited (by William Steinway, no less) with bringing about the adoption of the world’s first standard pitch for instrument tuning. He travelled constantly, both abroad and domestically, in fulfillment of his professional and civic responsibilities, and moved in the highest circles. Well-dressed and distinguished in appearance, Fuller was everywhere and knew everyone, and seemed to have a significant impact on almost everything he touched. Sadly, his non-stop pace and devotion to duty were not sustainable and he died at the age of 55, on October 10, 1896, from overwork and exhaustion.

Bas relief portrait of Gov. Levi Knight Fuller on his grave‘s memorial marker at Morningside Cemetery on South Main St. in Brattleboro. His wife Abby Emily Estey lies beside him there.

Bas relief portrait of Gov. Levi Knight Fuller on his grave‘s memorial marker at Morningside Cemetery on South Main St. in Brattleboro. His wife Abby Emily Estey lies beside him there.

In those 55 years of the late 19th century, he accomplished the work of several lifetimes, in an age when that scale of achievement was enabled and encouraged – a time and ethos we now celebrate in the Steampunk movement. Fuller Steam Division draws its references and personae directly from the life and times of Gov. Levi Knight Fuller and we feel this gives us a rare credence, a grounding that can deeply inform our creations and our story, crafting it from the material and archival evidence and circumstances which we uncover, both here in Brattleboro, Vermont and on the web. The word STEAM in our name is an acronym for the disciplines which Fuller pursued and from which we extrapolate with our work: Speculative Technology, Engineering, and Mechanics. We hope you will follow our adventures in Vermont Steampunk through the heritage of Levi K. Fuller. It promises to be an interesting journey!